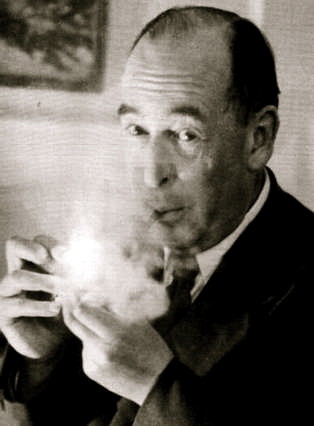

After just putting down, The Ministry of Fear, This Gun For Hire, and The Confidential Agent, I am once again reminded of what a compelling character this Graham Greene fellow is. He objected to being called a Catholic novelist, preferring to be called a novelist who happened to be Catholic. Most of his works are not religious in character although four are considered his 'religious novels'- The Power and the Glory, The End of the Affair, Brighton Rock, and The Heart of the Matter. Several of his earlier works put me in mind of 'spy stories' or 'thrillers' (though he described them as 'entertainments'). These stories are often set with war looming in the background. His books also remind me of Russian novels in that he deals with the internal struggle, as well as the need for physical survival. With many of his characters you feel as if you've seen into their soul, and perhaps can see your own more clearly. After reading Graham Greene, expect to feel guilty, dirty, and pure. Depressed, saddened, elated- spiritual & earthy- a deep sense of joy and the need to pray.

Graham Greene is able to portray struggles quite convincingly, perhaps because of and in spite of his own. He suffered from bipolar disorder, and once told his wife that he had "a character profoundly antagonistic to ordinary domestic life", and that "unfortunately, the disease is also one's material". He later separated from his wife, though never divorcing her. His first really successful novel was Stamboul Train (1932), which was later adapted as the film Orient Express (1934). He had many other such successes. Other items of interest include his recruitment by MI6, and his friendship with his neighbor Charlie Chaplin.

Greene is noted for a criticism he made of E. M. Forster and Virginia Woolf for not depicting the religious sense in which characters struggle. He stated that the result were characters who "wandered about like cardboard symbols through a world that is paper-thin". Greene often portrayed his characters grappling with the struggles of the soul. Something which Jane Austen masterfully portrayed, which Henry James showed somewhat.

Greene had his own struggles in life, angering some Catholics, while making others proud. The religious themes of his novels may be said to have taken a more humanistic tone in the latter part of his career, and he had no qualms with stating his political views. Despite this, he enjoyed having a bit of humor in his life, so when the the New Statesman held a contest for parodies of Greene's writing style, he submitted an entry under the pen name "N. Wilkinson" and won second prize.

Graham Greene once wrote of his Chiapas travels when he had taken shelter in a hut- 'a storehouse for corn, but it contained what you seldom find in Mexico, the feel of human goodness'. The man living in the hut gave Greene his bed, which was a 'dias of earth covered with a straw mat set against the mound of corn where the rats were burrowing...All that was left was an old man on the verge of starvation living in a hut with the rats, welcoming the strangers without a word of payment, gossiping gently in the dark. I felt myself back with the population of heaven.' Blessed are the poor in spirit: for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

Three By Graham Green (The Ministry Of Fear, The Confidential Agent & This Gun For Hire)